David Sloan Wilson is holding a white ceramic dog dish and making the rounds at the Lost Dog Café in Binghamton, New York. “Just like in church!” the biologist jokes, as he collects crumpled dollar bills on this snowy March afternoon. It is Yappy Hour, a fund-raiser for a project to turn an abandoned dirt-bike track into a dog park. The plan is a contender in Wilson’s ‘Design Your Own Park Competition’, a venture that he says is “richly informed” by evolutionary theory — and one of the many community projects that he is running, co-running or up to his neck in. As with most of Wilson’s endeavours these days, the motivation is twofold: to improve the quality of life in Binghamton and to study the city as an evolutionary landscape.

Wilson, who works at the State University of New York in Binghamton, has been a prominent figure in evolutionary biology since the 1970s. Much of his research has focused on the long-standing puzzle of altruism — why organisms sometimes do things for others at a cost to themselves. Altruism lowers an individual’s chances of passing its own genetic material on to the next generation, yet persists in organisms from slime moulds to humans. Wilson has championed a controversial idea that natural selection occurs at multiple levels: acting not only on genes and individuals, but also on entire groups. Groups with high prosociality — a suite of cooperative behaviours that includes altruism — often outcompete those that have little social cohesion, so natural selection applies to group behaviours just as it does on individual adaptations1. Many contend that group-level selection is not needed to explain altruism, but Wilson believes that it is this process that has made humans a profoundly social species, the bees of the primate order.

Wilson originally built the case for multi-level selection on animal studies and hypothetical models. But eight years ago, he decided to come down from the ivory tower and take a closer look at the struggle for existence all around him. A city — with dozens to hundreds of distinct social groups interacting and competing for resources — seemed to Wilson the ultimate expression of humanity’s social nature. If prosociality is important in the biological and cultural evolution of human groups, he reasoned, he should be able to observe it at work in Binghamton, a city of about 47,000 people.

The urban laboratory

Differences in prosociality, Wilson thought, should produce measurable outcomes — if not in reproductive success, perhaps in happiness, crime rates, neighbourhood tidiness or even the degree of community feeling expressed in the density of holiday decorations. “I really wanted to see a map of altruism,” he says. “I saw it in my mind.” And with a frisson of excitement, he realized that his models and experiments offered clues about how to intervene, how to structure real-world groups to favour prosociality. “Now is the implementation phase.” Evolutionary theory, Wilson decided, will improve life in Binghamton.

He now spends his days in church basements, government meeting rooms, street corners and scrubby city parks. He is involved in projects to build playgrounds, install urban gardens, reinvent schools, create neighbourhood associations and document the religious life of the city, among others. Wilson thrives on his hectic schedule, but it is hard to measure his success. Publications are sparse, in part because dealing with communities and local government is time-consuming. And the nitty-gritty practical details often swamp the theory; the people with whom he collaborates sometimes have trouble working out what his projects have to do with evolution.

At the Lost Dog, I ask city planner and frequent collaborator Tarik Abdelazim whether he understands why an academic scientist is taking such a proactive interest in the city. He leans against the bar, glass of wine in hand, and addresses Wilson. “I know you talk about ‘prosociality’, but how that connects to our good friend Darwin, I don’t know.”

Fellow biologists are also bemused. According to Wilson’s former graduate student Dan O’Brien, now a biologist at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, many have reacted to Wilson’s work with “a mixture of intrigue and distance”. That, says O’Brien, “is because he’s not doing biology anymore. He’s entered into a sort of evolutionary social sciences.” Wilson has acquired the language of community organizing and joined, supported and partially funded a slew of improvement schemes, raising the question of whether he is too close to his research. Has David Sloan Wilson fallen in love with his field site?

Binghamton is hard to love. Established in the early nineteenth century, it has long relied on big industry for its identity and prosperity — early on through the Endicott-Johnson Shoe Company and then through IBM, which was founded in the area. But the manufacturers mostly decamped in the 1990s, and since then the city has taken on an aimless, shabby air. Dollar stores and coin-operated laundries fill the gaps between dilapidated Victorian houses and massive brick-and-stone churches. A Gallup poll in March 2011 listed Binghamton as one of the five US cities least liked by its residents (see go.nature.com/tfdkqi).”It is a town that knows it is badly in need of a revival,” says Wilson. Even its motto, ‘Restoring the pride’, speaks of a city clinging to its past and ashamed of its present.

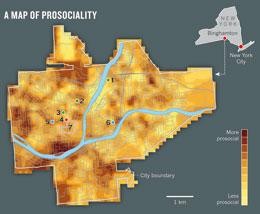

But as in any city, there is variation: some neighbourhoods are friendlier than others, some are more private and some feel downright dangerous. Wilson started his social experiment by measuring levels of prosociality in each neighbourhood. He and his research group gave surveys to teenagers from the local schools asking how often they helped or were helped by others. The researchers also dropped 200 stamped letters all over the city to see where people would help out a stranger by popping them into the postbox. They even recorded the density of Halloween and Christmas decorations. Wilson’s group used some of these data to create maps of the city’s prosociality2. Neighbourhoods in which people take care of each other appear as peaks, whereas selfishness creates valleys. There isn’t a straightforward correlation with any socioeconomic factor, Wilson found. Some of the most cooperative people were from “good, poor neighbourhoods”.

So Wilson decided to see whether he could raise up the prosocial valleys by creating conditions in which cooperation becomes a winning strategy — in effect, hacking the process of cultural evolution (see ‘A map of prosociality’). He set about this largely by instituting friendly competitions between groups. His first idea was a park-design project, in which neighbourhoods were invited to compete for park-improvement funds by creating the best plan.

But Wilson soon found out that field experiments in real cities can take on lives of their own: different neighbourhoods couldn’t get their acts together on the same schedule, so the competition aspect largely disappeared. Instead, he is now working on turning multiple park ideas into reality. The dog park is one. Another is Sunflower Park, the most advanced project to date, but still a sad, mainly empty lot surrounded by a chain-link fence. Children don’t spend a lot of time playing here. Undaunted, Wilson is raising funds and laying plans for a relaxing community space flush with trees and amenities. “In a year,” he says, “we will serve you a hot dog from the pavilion.”

Schooled for success

Wilson starts more projects than one man can usually handle. If there is an idea to paint a mural in a blighted area, Wilson wants in. The design can be a competition. And sure, he’ll have time to help. “No project should remain unborn,” he says. He then lets time constraints weed his overstuffed garden of initiatives.

Right now, education is winning a sizeable share of Wilson’s attention. He and his graduate students are working with school administrators in several locations to see whether they can improve student performance with programmes that reward good behaviour and encourage group cooperation. Treats, mostly donated by teachers, range from snacks and school supplies to odd but coveted items such as toiletries from hotels. Wilson insists that this approach is fundamentally evolutionary, pointing out that in 1981, psychologist B. F. Skinner described how reinforcement and punishment ‘select’ for desired behaviour3. Wilson is tweaking the school environment so that it selects for prosociality, and is hoping that the student culture will evolve accordingly.

The connection is less clear for Miriam Purdy, the principal of Regents Academy, a school for at-risk teenagers at which Wilson has been advising. When I ask how she sees evolution playing into the incentive programmes, Purdy surprises me and Wilson by saying that she doesn’t believe in evolution. But that doesn’t bother Wilson. It’s no matter, he says, if the principles work.

So far, it is hard to tell whether they do. Rick Kauffman, a graduate student who has spent so much time with students and teachers at Regents that he is a de facto staff member, says that no data have been collected on the incentive programmes because the rules have been adjusted weekly. Instead, he and Wilson are comparing the standardized test scores of Regents students with those of a control group of at-risk kids at the more traditional Binghamton High. A higher percentage of Regents students have taken and passed the state tests administered in January, and scientists and administrators alike are looking forward to the results of tests given later in the year.

Wilson has also been studying Binghamton’s religious institutions through an evolutionary lens. He is an atheist, but sees religion as a potentially positive source of community cohesion and a centre of meaning in people’s lives. He has written extensively about religion as an adaptation of groups4, and has been funded by the Templeton Foundation in West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, to study its effects. At the moment, he is trying to find out which of Binghamton’s 100 or so congregations are the most and least likely to flourish in the current cultural environment.

Wilson’s trait of interest is the ‘openness’ of churches. Traditional protestant denominations, of which Wilson is fond, tend towards openness: details of belief and moral codes are individual, arrived at after prayer and discussion. Newer, conservative churches that adhere strictly to the Bible as a literal text would be considered less open.

Wilson would like to understand from an evolutionary perspective why the membership of open churches in Binghamton is currently declining, but ‘closed’ churches are booming. Perhaps uncertain times create a fearful and socially isolated populace, interested in firm and clear guidance. Or perhaps closed churches uplift their members or focus on group solidarity and recruitment. When people’s economic and educational situations are better they may become attracted to more open churches. And Wilson says it is possible that the open churches, by allowing congregants to draw their own conclusions in matters of faith, predispose them to losing faith altogether.

Wilson hopes to test these ideas. The first congregation that he is studying is open, liberal and protestant: the Tabernacle United Methodist Church on Main Street. It has 100 regular members, who barely fill the hulking Victorian building. Last year, Wilson and two graduate students met extensively with the church’s Strategic Planning Task Force to craft a survey that was given to everyone on the church’s rolls in September.

The survey included questions about prosocial behaviour and about religious faith (such as “How often do you experience the following during worship services at this congregation? A sense of God’s presence, Inspiration, Boredom, Awe or mystery, Frustration, Spontaneity, A sense of fulfilling my obligation”). The researchers hope to expand the survey to the roughly 100 congregations across the city, and to create maps describing the ecology of religion in Binghamton.

The work has been met with curiosity and befuddlement. Richard Sosis, an evolutionary anthropologist at the University of Connecticut in Storrs, says that the work is wholly appropriate. “Religion is something that is human, generated from the human mind, which has been designed by natural selection.” He adds, “People are looking forward to seeing how this all unfolds, and the kind of success he has with it.” However, Ron Numbers, a historian of science and religion at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, is “a little ambivalent and confused”. Religious groups develop naturally owing to many historical factors, he says. “Going into some evolutionary account about this doesn’t add anything to our knowledge.”

“People are looking to see how this all unfolds and the kind of success he has with it. , ”

There is also the possibility that Wilson has become too close to the church. He has held so many community meetings in Tabernacle’s basement that he may even have increased the size of the congregation. I asked Wilson whether the effects he has had on the church will contaminate his study. He pauses for a long time before answering, “Not if you are monitoring what you are doing.” Wilson is upfront about his affection for the group. “I’d love this church to grow,” he says.

One of Wilson’s students on the religion project, Ian MacDonald, says that Wilson has “temporarily” allayed his fears about helping religious organizations. But MacDonald is uneasy about what will happen when they try working with closed, dogmatic churches that condemn homosexuality or teach women to obey their husbands’ every command. Wilson says that he is, “sympathetic to the ‘niche’ occupied by ‘closed’ churches”; he is not there to judge.

Long-term project

The playgrounds, schools and churches are but a few of Wilson’s ongoing schemes. Another is the West Side Neighborhood Project, which is surveying residents’ attitudes towards groups such as black people and students, before and after the creation of a landlord–tenant association and a student association. And he is even doing some work on the genetic level. In Wilson’s office in the city, 15-millilitre conical tubes hold DNA samples from elderly Binghamtonites who have been interviewed for their oral histories.

Each of the 47,000 people in Binghamton generates an infinite number of data points, from genomes to attitudes and habits of prayer. Wilson could spend the rest of his life — and those of several graduate students — studying and influencing lives here. But can he study the town and save it at the same time? Ben Kerr, a biologist at the University of Washington in Seattle, says, “In the sense of providing a deeper understanding, evolutionary biology has something to offer.” And he likes that Wilson is doing good in the community, but warns, “One has to exercise caution when moving from descriptive to prescriptive stances.”

Among social scientists — and that is arguably what Wilson has become — it is not uncommon to become involved with the communities being studied. Such involvement “might be a social good in itself, but it also helps you understand that community better”, says Kathleen Blee, head of sociology at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. “The desire to promote a social good may be stronger than leaving your field site untouched,” she adds.

Still, does one man have time to do both? Mary Webster, a resident who has been working on a park-design project in her neighbourhood, says that she initially saw Wilson as a professor with all the answers. Now, she says she realizes that he is “flying by the seat of his pants”. That “sounds about right”, says Wilson and, paraphrasing Einstein, he offers, “If we knew what we were doing, it wouldn’t be called research.”

It is past eight in the evening at Tranquil, one of the few upscale restaurants in town, where Wilson has invited members of the West Side Neighborhood Project. I quiz Wilson’s graduate students about how he could possibly pay enough attention to them with all the projects on his plate. But they are loath to say anything negative about the man who is buying them dinner. “He’s been better recently,” says one.

Meanwhile, Wilson disappears to take a call. A letter had been published in Nature that day5 defending inclusive fitness theory, a framework that seeks to explain the evolution of altruism, and that some evolutionary biologists have called unnecessary. The paper had made ripples in the press, and because Wilson made his name in such theoretical discussions, I assume that he is talking to someone about it. But when he returns, he says that he was on the phone with the religion reporter for the Binghamton Press & Sun-Bulletin, giving the scoop on an agreement to survey more congregations.

What seems like big news in the academic world has faded into the background for Wilson. There is so much to do right where he lives. “When you compare what I am doing here with furiously pounding away on my typewriter about that arcane debate, I think I made the right choice,” he says.